By Andrew Bzowyckyj, PharmD

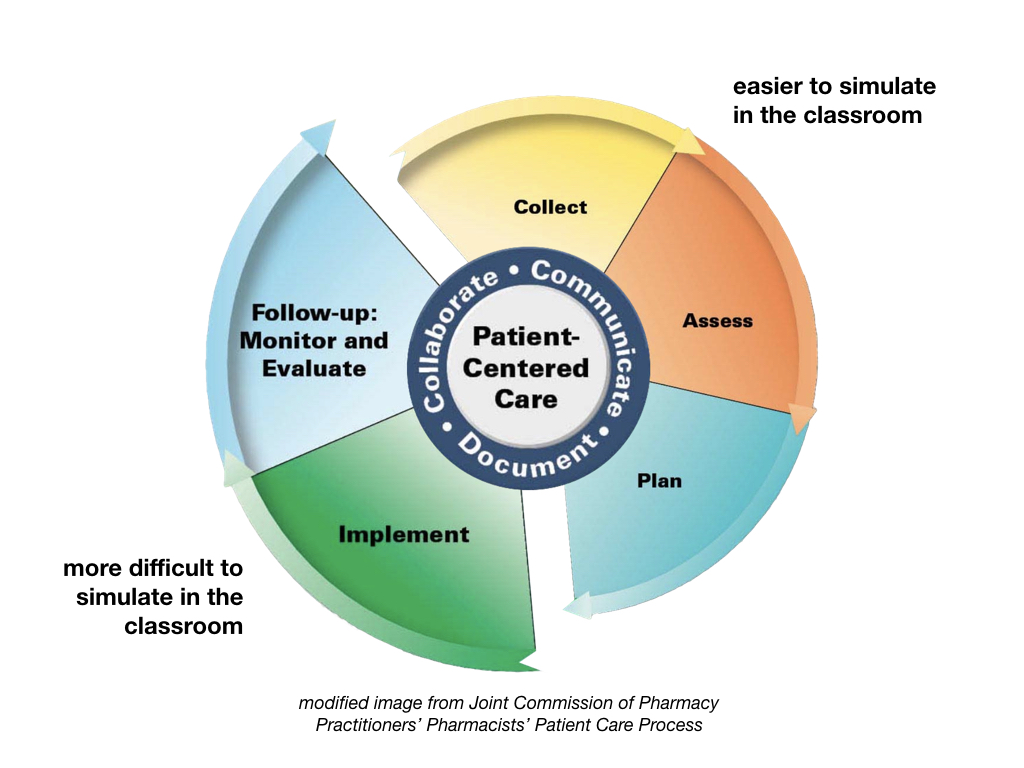

Reflecting on my experiences as a preceptor and student pharmacist, one of the most difficult concepts to apprehend is what it truly means to be an accountable pharmacist practitioner. The Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) released the steps to the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process (PPCP)1 that describes how students become accountable practitioners – moving beyond making recommendations to implement a plan of care and follow-up appropriately. This is consistent with Hepler and Strand’s philosophy of pharmaceutical care2 – a patient-centered practice in which the practitioner assumes responsibility for assessing all of a patient’s medications, medical conditions, and outcome parameters in order to identify, resolve, and prevent drug therapy problems, and is held accountable for this commitment.

Case-based discussions and assessments in the classroom increase students’ abilities to collect and assess patient-specific information in order to develop a therapeutic care plan, the first three steps of the PPCP. However, the latter half of the PPCP (i.e. implement and follow-up) are more difficult to authentically simulate in the classroom (e.g. factor in transportation barriers, clinic volume/availability, maximum number of covered visits per month when implementing a plan), and therefore must be emphasized further in experiential settings.

Students’ perspectives on what it means to be an accountable practitioner are highly dependent on the preceptors, pharmacists, and other health care practitioners they encounter during these highly formative years of experiential learning. To that end, it is important to evaluate what students encounter when they enter our practice settings.

Student Pharmacist Barriers to Developing into Accountable Practitioners:

- “Time Flies When You’re Having Fun” – Focus on Length & Duration of Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (APPEs): During the usual 4-6 weeks of an APPE, students are expected to orient to the site, develop their clinical skills in the particular disease state(s) encountered, expand upon their communication skills, and complete a laundry list of structured assignments, let alone develop their sense of professional accountability. In the ambulatory care setting especially, monitoring and follow-up can be especially difficult concepts for students to own since they will likely not be present to see the direct impact of their interventions.

- “I’m just a student” – A Professional Identity Crisis: Although a normal sentiment experienced by many students, it can be problematic if it interferes with completing the patient care process in its entirety. Experiential education can only be successful if students are able to experience all the tasks expected of them upon licensure. With this sentiment, it will be impossible to develop one’s sense of accountability to a patient-centered practice since the student may not feel ownership of patient care decisions.

- “Whose Line is it Anyway?” – Deferring to the Team: Although team-based care is a positive step, it can act as a barrier to developing one’s professional identity if the roles and responsibilities3 of each team member are not clearly understood by all (students and practitioners alike). Without developing a sense of accountability for implementing and following up on the patient’s care plan, the student’s perception of his or her role on the team may be solely observational or to answer questions only when asked, especially for “implementation” and “follow-up” since those responsibilities often overlap with other team members.

These are just a few examples of barriers that I have directly observed over the years, and I am sure there are many more. My next blog post in this series will discuss potential strategies for helping student pharmacists develop their understanding of what it means to be an accountable practitioner throughout their experiential training.

References

- Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process. https://jcpp.net/patient-care-process/ May 29, 2014. Accessed July 5, 2017.

- Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical Care Practice: The Patient-Centered Approach to Medication Management. 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/IPEC-2016-Updated-Core-Competencies-Report.pdf February 22, 2016. Accessed July 5, 2017.

Andrew Bzowyckyj is a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City in Kansas City, MO. Educational scholarship interests include student leadership development, reflection and reflective practice, and professional development of students into practitioners. In his free time, Andrew enjoys running, traveling and being a genuine foodie.

Pulses is a scholarly blog supported by a team of pharmacy education scholars.

3 Comments