By: Ramey W Hensley, PharmD Candidate; Jonathan Hughes, PharmD Candidate; Marissa Stephens, PharmD/MPH Candidate; Douglas R. Oyler, PharmD; and Jeff Cain, EdD, MS

Introduction

As generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) models become more popular, their application to pharmacy practice necessitates consideration of their role in pharmacy education.1 Several tools are available, including platforms designed for healthcare professionals. While GenAI tools can improve efficiency and decision support, they should not replace a pharmacist’s clinical judgment.2

Student pharmacists preparing to enter practice must learn to properly utilize GenAI technologies, including choosing appropriate platforms. This work evaluates the accuracy of five platforms when prompted with pharmacy inquiries.

Methods

Four pharmacy-related prompts were developed using an iterative process in which ChatGPT-5 generated initial prompts, a pharmacist reviewed them for clinical relevance, and the prompts were refined using principles from the Gemini Prompting Guide and CLEAR Framework (Table 1).3,4 In September 2025, each prompt was input verbatim as an individual query in five GenAI platforms, chosen for their free availability and relevance in pop culture and healthcare: ChatGPT-5, Claude Sonnet 4, Perplexity, OpenEvidence 2.0, and Glass 4.0 v2025-07-29. The accuracy of each response was independently rated by two reviewers (RH and JH) using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=mostly incorrect to 5=fully accurate), with adjudication by a third reviewer (MS). Median scores and interquartile ranges were calculated for each GenAI model, and group differences were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 1: Prompts used for queries in each AI platform.

| Prompt | Query Used |

| P1 – Antibiotic Selection | Act as a clinical pharmacist. A 45-year-old patient has community-acquired pneumonia. Culture shows Streptococcus pneumoniae. The patient has a penicillin allergy (rash). Formulary options: azithromycin, doxycycline, and levofloxacin. Identify the most appropriate antibiotic choice from the formulary and explain the reasoning, including allergy considerations and guideline-based evidence. If more than one antibiotic could be relevant, explain why one is preferred in this case. Explain what additional clinical data would guide the choice. Write in language suitable for pharmacist-to-medical team communication. Provide your answer in 3-4 sentences. |

| P2 – Metformin Counseling | Act as a community pharmacist counseling a patient. A patient arrives at the pharmacy to pick up their new metformin prescription. Create a patient-friendly explanation for starting metformin. Include benefits, common side effects, and what the patient should do if GI upset occurs. Write in clear, plain language at a 6th-grade reading level. Keep the explanation under 700 words. |

| P3 – Prior Authorization | Act as a clinical pharmacist. A patient needs PCSK9 inhibitor therapy after failing statins and ezetimibe. Draft a prior authorization letter for this patient’s new therapy. Include relevant clinical justification. Use a professional, formal letter style. Address the letter to an insurance reviewer, including the following sections: patient background, summary of prior treatments and failures, justification for PCSK9 inhibitor therapy based on guidelines, and a closing statement. This should not exceed one page in length. |

| P4 – Lithium Toxicity | Act as a clinical pharmacist. A patient takes lithium. They present with tremor, nausea, and diarrhea. Their serum lithium level is 1.8 mEq/L. Assess the severity of the patient’s presentation. Explain the likely cause. Recommend immediate management steps and monitoring. Include clinical reasoning and guidelines. Write at a professional clinical level. Provide your response in a structured assessment and plan format. Do not exceed 800 words. |

Results

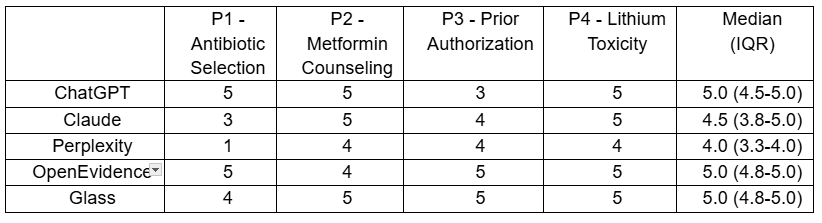

Accuracy ratings are presented in Table 2. Median accuracy ranged from 4.0 (IQR 3.3-4.0; Perplexity) to 5.0 (IQR 4.8-5.0, Glass, OpenEvidence). There was no statistically significant difference in rated accuracy between models (p=0.197). Overall, prompts 2 and 4 produced the most accurate ratings.

Table 2: Results of accuracy ratings.

Conclusions

Glass and OpenEvidence demonstrated the highest accuracy, although the difference was not statistically significant. All models performed well on patient-facing queries (drug counseling and toxicity assessment), but healthcare-focused models (OpenEvidence and Glass) outperformed others on clinically focused queries (antibiotic selection and prior authorization). This highlights a significant teaching opportunity: specific platforms may be better suited for different pharmacy-related tasks. However, all AI platforms are rapidly evolving, so their accuracy can change continuously.

Limitations of this work include the small sample sizes of pharmacy scenarios and GenAI platforms, and the use of students rather than pharmacist reviewers. However, multiple student reviewers were used, and the third-party adjudicator was only needed for 20% of scenarios.

Students can use activities like this to gain hands-on experience with GenAI platforms, developing the skills to critically evaluate their accuracy and application in clinical scenarios critically.

Do you have similar example activities?

References:

- Zhang X, Tsang CCS, Ford DD, Wang J. Student Pharmacists’ Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Pharmacy Practice and Pharmacy Education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2024;88(12):101309. doi:10.1016/j.ajpe.2024.101309

- Li L, Du P, Huang X, et al. Comparative Analysis of Generative Artificial Intelligence Systems in Solving Clinical Pharmacy Problems: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2025;13:e76128. Published 2025 Jul 24. doi:10.2196/76128

- “Gemini for Google Workspace. Prompting Guide 101: A Quick-Start Handbook for Effective Prompts.” Google; October 2024.

- Lo LS. The CLEAR path: A framework for enhancing information literacy through prompt engineering. J Acad Librarianship. 2023;49(4):102720. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102720

Author Bio(s):

Ramey W. Hensley is a fourth-year student pharmacist at the University of Kentucky. She aspires to pursue a community-based residency after graduation, with the end goal of entering pharmacy academia. In her free time, she loves watching football and spending time with family.

Jonathon Hughes is a fourth-year student pharmacist at the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy. Educational scholarship interests include neonatology, oncology, and pharmacy administration. In his free time, Jonathon enjoys hiking and traveling.

Marissa Stephens is a fourth-year student pharmacist at the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy and an MPH student in the Health Management and Policy concentration of the UK College of Public Health. After graduation, she aspires to pursue a PGY1 pharmacy residency with an end goal of working as a hospital-based clinical pharmacist, ideally with a role in health administration and policy development. In her free time, she loves trivia, movie nights with her friends, scrapbooking, and spending time with her family.

Douglas R. Oyler, PharmD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice & Science at the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy. His educational scholarship focuses on applying data-driven and implementation science principles, alongside emerging technologies, to strengthen pharmacy education and improve opioid stewardship. In his free time, he enjoys running, college sports, and spending time with his wife and three kids.

Jeff Cain, EdD, MS, is a Professor and Vice-Chair in the Department of Pharmacy Practice & Science at theUniversity of Kentucky College of Pharmacy. Jeff’s educational scholarship interests include innovative teaching, digital media, artificial intelligence, and contemporary issues in higher education. In his free time, he is dad to a pole-vaulting daughter, an extreme trail ultramarathoner. He is president ofFor Those Who Would, a 501(c)(3) charity in the adventure and endurance racing communities.

Pulses is a scholarly blog supported by a team of pharmacy education scholars.